On Sovereignty and Strategy

Creating Choices for Canada’s economic sovereignty – with Four Fund Futures

In a world awash in economic uncertainty, zero-sum negotiating and power politics, the idea of sovereignty is taking center stage.

Whether the debate is about tariffs, taxes, or trade agreements, the underlying theme is the same: control over one’s own future.

Sovereignty is more than just borders and policies; it is about financial independence and the ability to shape our own economic destiny.

One lever to achieve this is through a Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF), a tool that could give Canada more control over its financial future (also a lever closest to our wheelhouse here at Fuse).

But what would that look like for Canada? How would it impact our economy, industries, and daily lives?

To bring some structure and sobriety to the discussion, we framed four potential archetypes of a Canadian SWF and their implications for Canada, its citizens, and trading partners.

Putting the Fun in Sovereign Wealth Fund

This is not a political post in that this is not a “should do” exhortation; it’s a “could do” exploration. Before we can make decisions, we need to create choices. Let’s set some parameters for a productive and nuanced discussion around this often opaque yet significant topic.

What Exactly Is a Sovereign Wealth Fund?

When we hear about sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) in the news, they can often feel like a nebulous concept. These are huge pools of state-owned money invested globally to serve some grand national purpose. But what makes SWFs different from other types of state-controlled capital? To set the stage, let’s clarify what SWFs are not (SWFI 2023):

Foreign currency reserve assets held by central banks to stabilize exchange rates or manage balance-of-payments issues.

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) that operate as businesses, like utilities or transportation companies.

Government-employee pension funds, which are funded by contributions from employers and employees to ensure retirement security.

Assets managed for the benefit of individuals, like private retirement accounts.

Instead, SWFs are unique because they are designed to invest excess national wealth for long-term economic stability, diversification, and, in some cases, intergenerational equity. This distinction leads us to an important question:

What role should sovereign wealth funds play in shaping a country’s future?

This question is particularly relevant for resource-rich, productivity-poor countries like Canada. With the upcoming federal election, it’s worth considering what promises related to SWFs or national wealth management might mean for the average Canadian citizen.

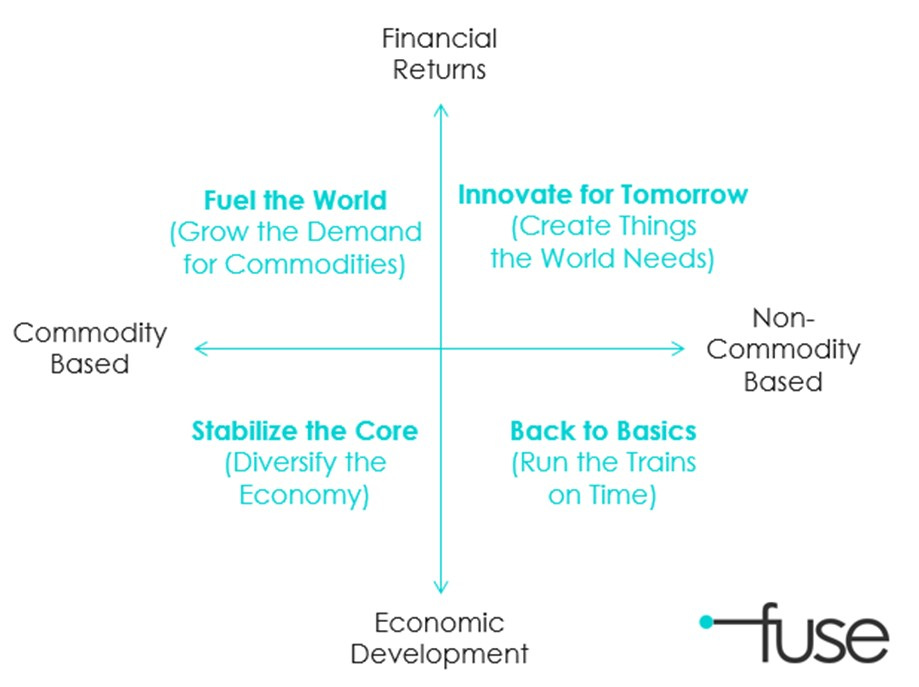

To help Jane and Jon Q Public think critically, we’ve sketched out a simple framework that highlights four possible strategies a government might pursue with state-controlled wealth. Each of these quadrants represents a different priority, with clear winners, losers, and trade-offs. Each axis represents a hot topic of conversation in the public press.

A Framework for Sovereign Wealth

When discussing a potential Canadian SWF, it helps to envision two primary tensions that shape how a nation might use its collective wealth. We can map these tensions onto two axes:

The vertical axis represents the primary objective: Financial Returns vs. Economic Development.

Financial Returns: One perspective views a sovereign wealth fund purely as an investment tool meant to grow the nation’s capital. Proponents of this approach prioritize high returns, diversification across global markets, and a clear separation from political or social objectives. The focus is on maximizing profit over the long term, often with minimal intervention in domestic industries.

Economic Development: On the other end, a sovereign wealth fund could be leveraged to spur domestic growth, innovation, and job creation. Instead of simply chasing returns, the fund can invest in targeted sectors—like infrastructure, manufacturing, or emerging technologies—to strengthen Canada’s economy from within. This can foster resilience, reduce reliance on volatile commodity markets, and address regional imbalances.

Why This Matters for Canada: Balancing these two extremes is crucial given Canada’s dual identity as a resource-rich and highly developed economy. Should a Canadian SWF prioritize global investment for profit, or should it catalyze homegrown industries and infrastructure? While one side might promise bigger financial gains, the other could offer broader socio-economic benefits—even if returns are slower to materialize.

The horizontal axis represents the economic context: Commodity-Based vs. Non-Commodity-Based.

Commodity-Based: Canada’s historical and current economic backbone involves resource extraction and export—oil, gas, minerals, lumber, and agricultural products. Choosing to position a sovereign wealth fund along this axis might mean doubling down on what Canada already does well: leveraging natural resources to generate immediate revenue. However, this path also heightens exposure to global price swings and environmental concerns.

Non-Commodity-Based: On the opposite end, a country can focus on diversifying its export profile (especially in high-value sectors) or boosting domestic industries that drive a persistent trade surplus. This might involve nurturing advanced manufacturing, technology, or services that create steady, less volatile revenue streams. For a sovereign wealth fund, that might translate into strategic global investments that reinforce non-commodity sectors—both at home and abroad.

Why This Matters for Canada: Resource exports have historically fueled Canada’s economy, but ongoing debates center around sustainability, diversification, and the transition to a lower-carbon future. If Canada aims to maintain a significant trade surplus in a rapidly evolving global market, it must decide whether to sustain its commodity focus or invest heavily in emerging industries. A Canadian SWF could tip the scales one way or the other—shaping national economic priorities for decades to come.

This gives us four quadrants, each representing a different approach to managing sovereign wealth. Here’s how they break down:

Plotting these two tensions—Financial Returns vs. Economic Development on one axis and Commodity vs. Non-Commodity on the other—creates four distinct quadrants. Each quadrant paints a different vision for how Canada might manage its sovereign wealth:

Do we maximize short-term revenues and global competitiveness in commodities?

Do we invest heavily in cutting-edge industries and future-oriented development?

Should we diversify the economic base to stabilize employment across regions?

Or should we focus inward to enhance public services, infrastructure, and overall quality of life?

By laying out these questions visually, we can more easily compare the risks and rewards of each approach. Most importantly, it underscores that there is no one-size-fits-all model: each choice comes with trade-offs that reflect differing national values, priorities, and visions for the future.

Top-Left: “Fuel the World” (Grow the Demand for Commodities)

Description: This strategy focuses on maximizing the global demand for Canada’s natural resources, such as oil, gas, and lumber. Governments would prioritize marketing Canadian exports and investing in infrastructure to support global competitiveness.

Who Wins: Commodity producers, energy companies, and resource-heavy provinces like Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Who Loses: Canadians in other sectors may feel left behind as economic diversification is deprioritized.

Trade-offs: While this approach delivers quick revenue and job growth, it risks over-reliance on commodities, leaving Canada vulnerable to price fluctuations and global shifts away from fossil fuels.

Example: Established in 1976, ADIA exemplifies a pure focus on financial returns from commodity wealth. It takes Abu Dhabi's oil revenues and invests them globally. ADIA demonstrates how a resource-rich nation can build global financial strength while maintaining a singular focus on portfolio returns.

Top-Right: “Innovate for Tomorrow” (Create Things the World Needs)

Description: Leverage trade surpluses to fund innovation in technology, clean energy, and other industries of the future. This strategy invests in creating products and services with global demand.

Who Wins: Urban centers, tech industries, and younger Canadians looking for sustainable careers.

Who Loses: Resource-based communities may feel alienated as traditional industries lose focus.

Trade-offs: This long-term strategy may require higher taxes or public debt to fund R&D, with benefits taking years to materialize.

Example: GIC invests Singapore's trade surpluses through a global investment portfolio, focusing on future-oriented sectors and emerging technologies. With no domestic mandate, it purely pursues financial returns through global investments strategies, showing how a trading nation can leverage its economic success.

Bottom-Left: “Stabilize the Core” (Diversify the Economy)

Description: This approach focuses on reducing dependency on commodity exports by strengthening other economic sectors like manufacturing, agriculture, and domestic energy.

Who Wins: Broader regions, including smaller towns and provinces reliant on stable employment, benefit from a more balanced economy.

Who Loses: Commodity-focused industries may struggle with reduced government support or investment.

Trade-offs: Slower economic growth in the short term as resources are redistributed from high-performing sectors to build resilience.

Examples: Abu Dhabi's Mubadala uses oil wealth to drive domestic economic diversification. While the fund seeks sustainable returns, its primarily focuses on developing local industries, creating jobs, and building non-oil sectors. It offers an example of using commodity revenues primarily for domestic economic development.

Bottom-Right: “Back to Basics” (Make the Trains Run on Time)

Description: Use trade surplus revenues to modernize infrastructure, healthcare, and education, improving productivity and lowering the cost of living.

Who Wins: Average Canadians see tangible improvements in public services and infrastructure, while small businesses thrive in better local conditions.

Who Loses: Export-focused industries may feel neglected, and the approach could lack big financial returns for future generations.

Trade-offs: Citizens experience immediate quality-of-life improvements, but there’s a missed opportunity for global leadership in emerging industries and soft power influence.

Example: There are no obvious and clear cut examples here, which is interesting in and of itself. This model is the hardest to do well because of the difficulty of staying focused on domestic investments with timelines to return that exceed the average election cycle. However, this model seems to evident in public opinion; the desire to have Canadian pension funds investment domestically is grounded in this quadrant. Having an internally-focused SWF that is constitutionally mandated to deliver domestic quality-of-life improvements would be one approach to satisfy these needs.

What This Means for Voters

As Canadians head to the polls, this framework for understanding sovereign wealth offers a way to decode political promises. When a party talks about leveraging Canada’s natural resources, they’re likely leaning toward the “Fuel the World” quadrant. When the focus shifts to innovation, think “Innovate for Tomorrow.” Promises to support small businesses or rural areas often reflect a “Stabilize the Core” approach, while pledges to improve infrastructure and public services point to “Back to Basics”.

Each strategy has its merits and risks, but the key for voters is understanding the trade-offs. For instance, a focus on short-term financial returns might boost jobs today but leave future generations grappling with volatility. Conversely, long-term investments in innovation or efficiency may take time to pay off but position Canada as a leader in global markets.

These options are not necessarily mutually exclusive, exhaustive or even complete. They are a quick back-of-the-napkin anchoring exercise, meant to spark curiosity and encourage Canadians to ask better questions about the promises they hear. Sovereign wealth management is a complex topic, but at its heart, it’s about choices: What kind of country do we want to build, and who benefits from those decisions?

So, the next time you hear a politician talking about using Canada’s natural advantages for greater independence, think about which quadrant they’re aiming for and ask yourself: Is this the future I want for Canada? What am I truly getting, and what am I willing to give up to get it?

Got other ideas, let’s hear them! We’re listening at hi@fusestrategy.co.